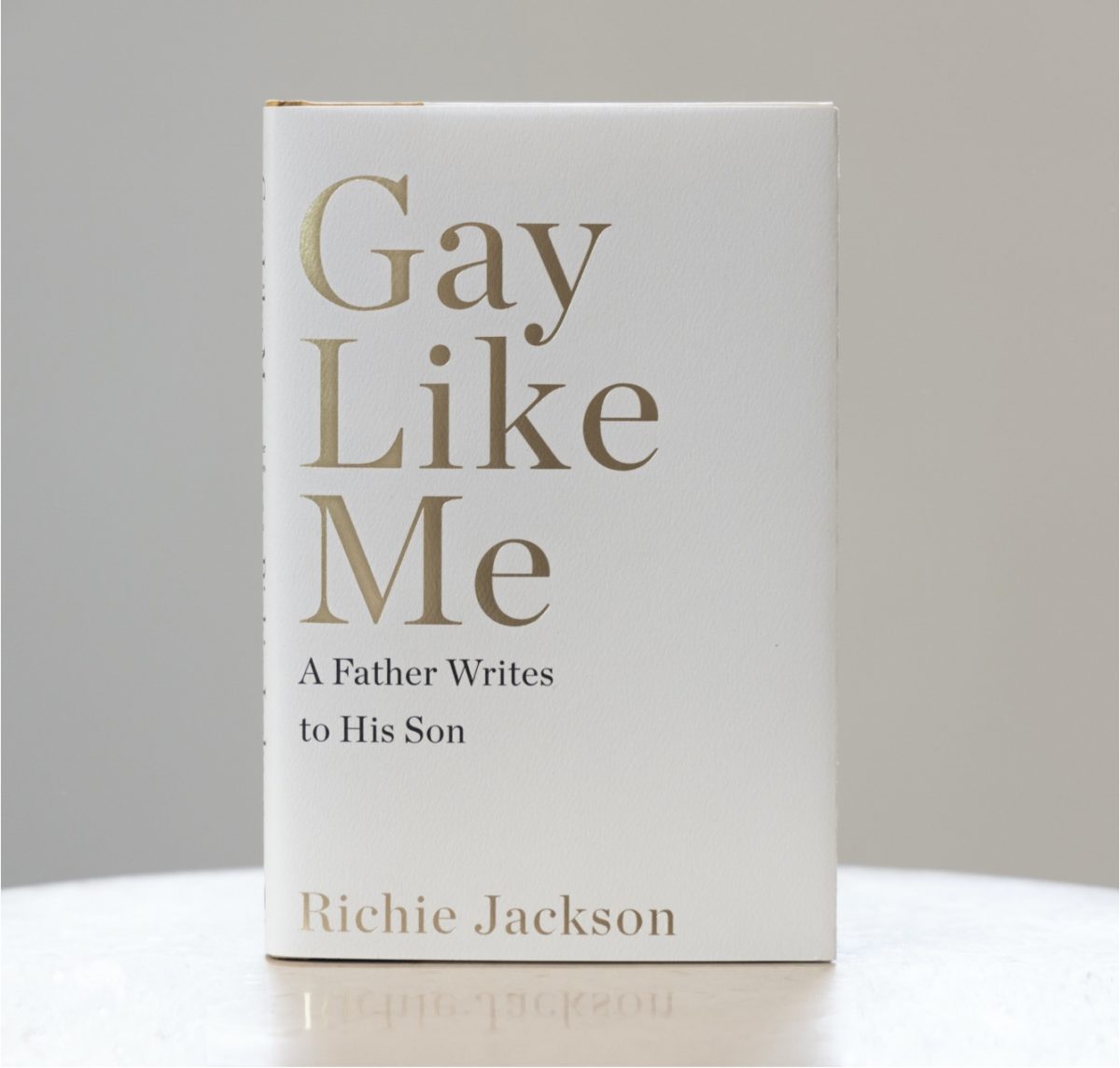

Now available from Harper Collins is Richie Jackson‘s Gay Like Me—a poignant and urgent love letter to his son. In the new book, the award-winning Broadway, TV and film producer reflects on his experiences as a gay man in America and the progress and setbacks of the LGBTQ community over the last 50 years.

“My son is kind, responsible, and hardworking. He is ready for college. He is not ready to be a gay man living in America.”

When Jackson’s son born through surrogacy came out to him at age 15, the successful producer, now in his 50s, was compelled to reflect on his experiences and share his wisdom on life for LGBTQ Americans over the past half-century.

Gay Like Me is a celebration of gay identity and parenting, and a powerful warning for his son, other gay men and the world. Jackson looks back at his own journey as a gay man coming of age through decades of political and cultural turmoil.

10. The Lion King – 1997

The Lion King was the first Broadway show we took our older son to when he was four years old. I can’t tell you anything about that Saturday afternoon performance because we didn’t watch the show – even better – we watched our son watch the show. He was mesmerized.

9. Love! Valour! Compassion! – 1995

One of the many blessings about being gay is the creation and cultivation of our chosen families. Our groups form often out of necessity, shunned by our own families, seeking a place to belong. Love! Valour! Compassion! beautifully depicts one such family.

8. Angels in America – 1993/2018

In 1993, when I saw Tony Kushner‘s Angels in America, it pointed us forward with intelligence and rage, humor and compassion. We watched that rage and fear being embodied in the staggering performances of Joe Mantello, Stephen Spinella and Ron Liebman.

Watching Opening Night of the extraordinary 2018 Broadway revival, produced by my husband Jordan Roth, the play was just as powerful as the first time I saw it and showed what a profit Tony Kushner was.

7. Falsettos – 1992/2016

When I saw the original Falsettos on Broadway, I thought “The Baseball Game” was the funniest musical number I’d ever seen, it still is. Years later, while watching my husband Jordan Roth‘s 2016 revival, and now as a parent, the lyrics in the song “Jason’s Bar Mitzvah” resonated with me in a new way: “Kid, do you know/How proud I am?/…You hold my dreams/Kid, I burst at the seams/’Cause of you”.

6. Grand Hotel – 1989

Grand Hotel, for me, represents the best of what actors can do; but also the devastation and savagery of the AIDS epidemic, what extraordinary souls we lost, and the hole that cannot be filled. Watch Michael Jeter and David Carroll in this clip and see what I mean.

5. Black and Blue – 1989

I was an assistant at Gatchell & Neufeld, a theatrical general management firm, when Black and Blue premiered on Broadway. I must have seen it four times. It was brimming with extraordinary talent including Ruth Brown, Linda Hopkins, Bunny Briggs, and Savion Glover. I was deeply moved by the curtain call, which was staged like the passing of the torch from one generation to another.

4. La Cage Aux Folles – 1983

I was a freshman at New York University and we were offered $10 tickets to see La Cage Aux Folles on Broadway. I took my mom and we sat in the very last row of the balcony of the Palace Theater. It was the first time I had heard the song “I Am What I Am,” which has since become an LGBTQ anthem. But, though I love that number, “Song On The Sand” was the most revolutionary aspect for me. Two men singing a love song to each other in a big Broadway musical.

3. Torch Song Trilogy – 1982

When I was seventeen years old, I hadn’t come out yet, and I got a lifeline from an ally- my mother. She had seen a Broadway show that she loved so much that she bought more tickets on the way out to take me. She told me it was an amazing play, with an extraordinary performance by the lead actor who was also the playwright. His name was Harvey Fierstein and the groundbreaking play was Torch Song Trilogy. At the end of the play, the mother says to her son (played by Harvey) that being gay is a sickness, and that if she knew he was going to turn out gay, she wouldn’t have bothered.

After the show, my mother said to me, “If you ever came home and said you were gay, I would never react like the mother in the play.” It was her own humanity that got her to use a Broadway play like a crystal ball and show me my future. It showed me a life that could be possible for me.

Thirty six years later, I produced the revival of this life-changing play on Broadway. And on Opening Night, I sat next to my parents, my husband and my son in the very same theater I saw it in all those years ago.

2. Evita – 1979

In 9th grade my Social Studies teacher, Mr. Shaldone, announced we were going on a class trip to New York City to see a Broadway show. He let the class vote on what show. We could see the 1979 revival of Oklahoma or a new show that was just in previews so he didn’t know much about it. It was called Evita. The class chose Evita and we got to see the remarkable Patti LuPone.

1. Pippin – 1972

Pippin was the first Broadway show I ever saw, I was 7. We sat in the very first row. I was captivated, Ben Vereen was the perfect introduction to the magic of musical theatre.

This article was originally published on BroadwayWorld.com

I had a singular and pure impetus for my book, Gay Like Me. As a gay man and the father of a gay son who was readying himself to move out of our home for college, I had to write a letter to him about what it means to be a gay man and what it takes to be a gay man in America. I chose a narrow lane and the structure of a letter. I needed to tell our son everything I know—everything he needed to know—as he stepped out into the world on his own.

But what could have felt academic or textbook-like would not work. Writing a letter to my son prevented me from editing out or smoothing over any of my own harrowing history or of the LGBTQ community’s. I was completely honest and held nothing back.

I took a risk in being vulnerable enough to share all the things I had previously kept from him so he would feel safe. When is it a good time to tell your child about the plague you lived through? He never knew we traveled with his birth certificate on vacations in case our parentage was ever questioned at an airport or worse, a hospital. But I knew by being fully exposed, the outcome would be far more meaningful to his life.

If I told him all of my mistakes, everything I did—the good, the bad, the secret—he would not repeat them. He would not fall into the same traps I did. While I can’t prevent him from making his own mistakes, I can hopefully save him from mine.

The most challenging part of the experience was building up my emotional stamina to revisit so many painful memories. I was mining the most difficult parts of my life – my fourth grade gym teacher calling me a faggot, my first bruising sexual experiences with young men who were filled with shame, the birth story of our premature twin boys and one of them dying.

Having never written a book before, I had no writing process. I stared at the computer and it felt a lot like my everyday life—it didn’t feel creative sitting an arm’s length away from my words. I didn’t know how best to excavate what I knew I wanted to write. Then I adapted my daily ritual of reading at dawn before my family wakes up to my writing time and ditched my computer.

My good friend, the acclaimed writer Harvey Fierstein, counseled me, “If you write an hour a day, that’s a good day.” That freed me up. I took pencil to paper, and at 5am every day, I hand wrote my love letter to being gay, to being a parent, to being in love. That quiet early morning time gave me the vulnerability required, my pencil was a more direct line from my heart to the page.

The payoff was immeasurable. I am confident I left nothing unsaid. All parents should do this for their child as they set out into this tumultuous, wondrous world.

This article was originally published on Town&CountryMag.com

In this exclusive excerpt from his new book Gay Like Me, Richie Jackson writes to his son about what it takes to be a gay man in America. He addresses the gift of being gay as well as the guard the gay community must always have up.

I am so excited for you — and filled with anxiety — that you are leaving our home to live as a gay man in New York City. High school is over and you are college-bound. You are kind, responsible, and hardworking. You are ready for college — but are you ready to be a gay man living in America?

You were 15 when I watched with joy as you began to spend time with another young, free boy. All those first courtship steps, your adolescent fervor, your singular focus, your trying on how to be part of a couple. I was thrilled not only because you had a friend with whom you were partaking of all the teenage rites of passage of first blush, but specifically because the object of your affections was a boy. My greatest wish for you was for you to be gay, for you to have a gay life, for us to have that central part of ourselves in common. Being gay is a gift. It’s the world revealing itself in all its glorious otherness, saying go it your own way, make it yours. The revelations are endless. There are no expectations of what you need to be or to do. It is the blankest of canvases. It’s freedom. It’s the gift of possibility.

I am so happy you are gay. There is so much about being gay that I am eager for you to experience. The amazingly diverse community that you are now a part of and that is now a part of you — the brilliant, funny, creative, inventive, courageous, wicked, strong, heroic lives you are among. The chance to love and to be loved by an extraordinary individual. The creativity that will permeate your day because there is no set course you must follow. I am thrilled for the flight ahead of you; I am wary of the fight ahead of you.

When I rejoiced that you were gay, I was really wishing for the good parts — the community, the camaraderie, the creativity. The incredible beings who populate our community, who against all odds are themselves. But you can’t be gay with just the good parts: Your life daily will be touched by all the difficult parts, too. The fight, the struggle, the challenges, will make it even more valuable, even more worthy. And as you set out on your gay adulthood, I know you have mistakes to make, lessons to learn, and that you will seek your nourishment your own way. As one of the people responsible for bringing you into this world, and for your well-being, I have to share what I know as a gay man, to provide you some tools that I didn’t have, and to prepare you for what may lie ahead.

One of the confounding things about being gay in America is what the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois described as double consciousness. He was referring to Black Americans when he wrote: “One ever feels his two-ness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” You are an American; you do all the things Americans do; you even have the dream. But America doesn’t want you, doesn’t accept you, is systematically attempting to erase you. Schools don’t teach about you; laws don’t fully protect you. The America you think you are a part of is a mirage. You must every day keep a certain clarity about yourself yet remain keenly aware of America’s vision of you. You need that dogged strength that is partly the spirit of protest and partly the shoring up of your gayness so that your gay line of vision is clear, beautiful, strong. Living as a gay man means holding this double vision, and I have to attempt to show you how to make both your visions strong.

As you prepare to go to college as a gay man facing the world, a gay man in America, it is critical that I tell you everything I know — everything that I have learned, every rise and every depression, so much that I have kept to myself so that you would feel safe. All of that I have to tell you now. How else will you survive? I need to show you how to keep your body safe, your heart strong. I need to get you angry, and even scare you a bit. And though it may seem that I am clipping your wings just as you are about to set off, I am merely watching out for you from my vantage point, ensuring that you take flight safely, to soar freely.

This article was originally published on Out.com

I am old enough to remember when we were “Gay”; now we are “LGBTQ.” Our combined identities are not just stripes on our flag so everyone feels represented; our initialism is our chain linking us together— we rise and fall, survive and thrive, only if we all do. Those who want to do us harm aren’t parsing out our letters to simply pick off just one of us. They strike first at the most vulnerable and continue down the line.

You are leaving home and entering a riptide of hate, and we taught you as a child never to swim directly into a riptide, always swim with it, parallel to where you want to be. Not so with this fierce current. Here you have to join the battle to fight just as I did. The only way to safe shore is forward. It is our collective responsibility to fight every injustice and to defeat every bad bill everywhere. This demands all our participation. Being gay is, still, acting up and fighting back.

Your civic duty now includes your volunteering for organizations like the Human Rights Campaign, the largest national LGBTQ civil rights organization; or Lambda Legal Defense, the national legal organization committed to achieving full recognition of the civil rights of LGBTQ people and everyone living with HIV; or The Trevor Project; or grassroots organizations like ACT UP, still united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis; or new groups you can seek out.

Being a good gay citizen requires voting. As important as allies are, they aren’t LGBTQ-centric voters as you must be at every election for every office, from the Board of Education officials up to the president of the United States. Do not let anyone dismiss your activism as identity politics. That charge usually comes from straight people treating us like a distraction.

Identity politics doesn’t narrow your focus; it widens your expectations of candidates and forces them to directly address our community and our issues. It claims your rightful attention.

Identity politics doesn’t silo you. The power of identity politics is to find what other identities you identify with. Look for the winning coalition that will bring liberty and justice for all. If we are to restore and expand our rights, then we also have to recognize that we are not unique in being under attack. Women, people of color, immigrants, the poor, also have the same stake as we do in who the next president will be. To be sure, we have common oppressors and mutual goals. We all need to ensure our individual communities are being heard, while also listening and standing up for one another. Then eventually we must coalesce around the winning vision that includes all of us.

The 2020 Democratic presidential primary is thrilling due to the diversity of its candidates, including the extraordinary Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and a gay man. There is no way to be cavalier about a gay man being a top-tier contender for the presidency. It is remarkable. And when someone tries to use Mayor Pete as proof there is no more homophobia, just point out where racism stands after we had our first black president for eight years.

Beware too the Republican allies who tell you they are fiscally conservative but socially liberal. They are telling you that our community will always come second to them. Their wallet, their tax rate, dwarfs our right to exist. An alleged LGBTQ ally who votes for a Republican presidential candidate knowing full well that contender will appoint conservative judges, especially to the Supreme Court, is not allied with us.

Who is elected at every level has consequences. An elected county clerk in Kentucky defied a federal court order to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples because of her own personal religious beliefs.

Vote as if your life depends on it, because it does. Vote as if someone else’s life depends on it too, because it does. Ask which candidate will aggressively and progressively improve the lives of LGBTQ people. Think about all the Supreme Court cases that have had profound and real effect on our lives—Bowers v. Hardwick rendered us noncitizens, and seventeen years later Lawrence v. Texas overturned Bowers, finding that lesbians and gay men have the same fundamental right to private sexual intimacy with another adult as heterosexuals do, and the marriage cases: United States v. Windsor in 2013 and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

Being a good gay citizen means being informed. I remember when the only place I was able to get my gay news was from The Native. Now articles about us appear in mainstream media with some regularity, but not everything that matters to us makes it in, so stay informed, and by LGBTQ journalists and LGBTQ news outlets. I’ve bought you subscriptions to The Advocate and Out magazine. Read websites like New- NowNext, the HuffPost’s Queer Voices, them., and Queerty; blogs like Towleroad and JoeMyGod. Follow LGBTQ journalists and thinkers on Twitter, like Zach Stafford, Jennifer Finney Boylan, Tim Teeman, Scott Bixby, Saeed Jones, Chase Strangio, Zack Ford, Sarah Schulman, David Artavia, Andrew Sullivan, Jonathan Capehart, Rachel Maddow, Tre’vell Anderson, Phillip Picardi, and Janet Mock. Look for the regional LGBTQ periodicals and websites wherever you live.

LGBTQ people span every race, religion, and culture. We are women, people of color, people with disabilities, immigrants, refugees. Don’t get caught in the senseless competition between marginalized groups as to who is more oppressed. The Oppression Olympics serve one group and one purpose—the oppressors, and to divide and conquer.

Remember what your Gay-Straight Alliance adviser pointed out when he told you that your committed student group wasn’t just for the kids inside the room, but was especially for the kids not yet ready or able to walk in the door. He said they were comforted just knowing your group existed. Keep going to Pride for the people who can’t. For those LGBTQ people not yet out, oppressed, who live in fear for their lives or livelihoods, who live in countries that would condemn and kill them—go to Pride for them. Show them by our vast numbers that what awaits them is a sea of acceptance and love.

I was blessed to have Harvey be the gentle (and sometimes not so gentle) guide for my gay life. AIDS robbed us of a lifetime of mentors, a devastating tragedy for our younger generations that missed out on their wisdom, knowledge, experiences, and fabulousness. That is one void we all can fill. The Point Foundation provides mentorship and scholarship funding for LGBTQ students of merit. You aren’t too young to start helping someone else. Don’t wait till you are in the middle of your life or at the end of it to start to help. There is no such thing as giving back, no such thing as paying it forward. Part of living, part of the doing, is helping other people. It’s not a debt; it’s the purpose. You can’t consider yourself successful if you aren’t helping someone else to get where you are. And you are never too young to start.

It has been the work of my adult life to understand deeply that the best part of me is reviled, my proudest aspect assaulted. I’ve had to ward off and fight back violence, disease, hate, and condemnation. I’ve worked to amplify my own being, not just for the right to exist, to be left alone, but to thrive and to shine. The pursuit of happiness isn’t just a declaration; it’s a dare to live. It’s not just about law; it’s about my potential. It’s not only about access; it’s about ascending. To live as fully gay as possible is how I am most alive.

Every gay person is a wonder. It takes enormous effort to go from cocoon to butterfly and to stay aloft daily, to defy your parents’ expectations, your religious teachers, to get through childhood knowing you are different, and to stand up and say this is me when everything around you tells you to be something else, to withstand the daily reminders that make you feel isolated.

The reason the straight world tries to diminish us, to demean our differences, is not because we are defective or worthless. Quite the contrary: it is because they know how powerful being gay makes us.

We don’t learn about ourselves in history class, don’t learn sex-ed; we are bullied and bruised by classmates.

We sit in Sunday schools that tell us we’re sinful. We are minorities within our own families, disappointments to our parents and to our ancestral status quo. We are subjected to the shifting wins and whims of a biased American electorate and a jaundiced judiciary.

Each of us is keenly aware that our perception of ourselves stands in stark contrast to the field of vision of our country. Most of this abuse takes place while we are children. What is in our hearts, what is most special about us, we are told is wrong and to suppress it. How remarkable it is that, among all these terrors, we still come out. We still rise and say this is me. Our power to resist, persist, act up, fight back, is in fact the spirit of an extraordinary species of people.

I have invested my time in unlocking what gay had in store for me. I believed since I was a child that for some reason I was chosen, and discovering what that meant, unraveling its glory, understanding its mystery, and respecting its power is why I get to say I am your father. I didn’t hide, ignore, or scrub off my gayness at any part of my life. The theme of my life has been to fulfill all the parts of my gay self and to imbue the world with more gay.

You don’t have to be gay like me, but you do need to be sufficiently gay your own way. I didn’t do everything right—and I have the scars to show for it. But you have been chosen too, and it’s not an accident; it’s your power. What is different now isn’t all better, and what’s worse is just as scary, so our lives will look very different and painfully similar.

Keep focused your two visions—in one, the struggle and complications; and in the other, all your worthy, glorious gayness. At four years old you were prescribed glasses—a health remnant of your prematurity. I chose glasses for you that you hated, and Daddy Jordan took you to find ones that you liked and would actually wear. You settled on a particular brand, and when the salesclerk showed you the sample with all the color options, you said you wanted that exact pair. You chose rainbow glasses and have ever since worn the same multicolor, vibrant frames. You have literally looked out of rainbow glasses your whole life. Your glasses have always helped you to see the world better.

This article was originally published on ThriveGlobal.com